He who hesitates is lost. And so the crafty politician from Madhya Pradesh – Arjun Singh – failed to seize what he was ‘destined’ for.

By ND Sharma

Arjun Singh, who died on March 4 at 81, was a phenomenon in Indian politics: a master in the art of creating illusions, which people took for reality even decades later. He is still referred to as an able administrator; all he had done was to patronise a band of ferociously loyal IAS and IPS officers and administer through them more like an autocrat than a democratically elected leader. He had no patience for niceties of rules and regulations.

Rajiv Gandhi had, for instance, enacted the law to establish Navodaya Vidyalayas in rural areas with a view to imparting quality education to village boys and girls at par with their counterparts in cities. The Act provides for starting a Navodaya Vidyalaya only after the school and hostel buildings, to prescribed specifications, were constructed. The Centre provided the funds for this. Rajiv Gandhi’s human resource development (HRD) minister PV Narasimha Rao went ahead with the Navodaya Vidyalayas in states, one in Madhya Pradesh also, in compliance with the law and rules. But Arjun Singh, as HRD minister in the Narasimha Rao government, opened Naovdaya Vidyalayas in Madhya Pradesh by the dozens without a single one having its own school or hostel buildings as per the specifications.

At least in one Navodaya Vidyalaya in Rajgarh district, a dilapidated garage hired from an old Congress leader, was being used as hostel for the children. Similarly, as many as 16 Central School teachers appointed at different places in and outside Madhya Pradesh were attached to the Central Schools in Bhopal city at a particular time. If the schools where these teachers were supposed to be teaching suffered in the process, it was none of his concern. (Some of Arjun Singh protégés were sent to faraway places when Dr Murli Manohar Joshi became HRD minister in the NDA government. Joshi had made the transfer/attachment rules pretty stringent).

In fact, Arjun Singh emerged in Indian politics at a time when the euphoria of establishing a people’s republic for the welfare of the people had started evaporating and a commitment to democratic values was on the decline. He was almost a genius, but he used his genius to subserve his own fiefdom, caring little for established democratic norms. He was a friend, philosopher and guide to Muslim leaders but he is not known to have done anything tangible for the community; never allowed Muslim leaders to gain importance in Madhya Pradesh. Nor could he reconcile to the emergence of leadership among the Dalits, adivasis and OBCs; still, he was hailed as the messiah of the dalits, adivasis and OBCs. Media management was one of his strongest points.

After the 1980 Assembly elections in Madhya Pradesh, he was one of the three candidates for the leadership of the Congress Legislature Party (CLP). A majority of party MLAs favoured Shivbhanu Singh Solanki, a tribal MLA from Jhabua, but Arjun Singh became the chief minister by taking the help of Sanjay Gandhi who was then calling the shots in the Congress. One of his first acts as chief minister was to enact the law for creating a trust for the management of Bharat Bhavan, the premier multi-arts complex. He made himself and Ashok Vajpeyi, a slavishly loyal IAS officer, trustees ‘for life’, not bothering whether his action militated against the very concept of democracy. A ‘Note’ for removing this feudal proviso from the Bharat Bhavan Trust Act was prepared by Motitlal Vora when he became chief minister in the late 80’s but he did not dare go further. The Act was amended by the BJP government under Sunderlal Patwa.

As the OBC factor started emerging in Indian politics, Arjun Singh constituted a one-man commission, with Ramji Mahajan as its chairman, to identify OBCs in the state. Mahajan did a commendable job in identifying OBCs in each district of Madhya Pradesh and came out with two volumes after working hard for over three years. Arjun Singh made each department of the state government issue notifications reserving 14 per cent of seats for the OBCs, including in admissions to the medical colleges. A student of Indore medical college challenged the notification and the High Court issued interim injunction in respect of admission to that particular college till further hearing. Arjun Singh promptly made each department of the government issue another notification cancelling the previous one. No effort was ever made to get the interim injunction issued by the Indore bench of the High Court vacated. That was the end of Arjun Singh’s concern for the OBCs.

Arjun Singh got the opportunity to help an OBC become chief minister in 1993. He had even made a promise to Subhash Yadav, a long-time loyalist. Digvijay Singh, PCC chief and a member of Lok Sabha, had publicly announced that he was not in the race for chief ministership. However, Digvijay Singh jumped into the fray at the last moment, ostensibly on an assurance from Arjun Singh who commanded the largest chunk of members in the Congress Legislature Party (CLP). Arjun Singh held a meeting of his supporters at his government-allotted house, drove to the chief minister’s residence where the meeting of the CLP was to be held, declared that his supporters favoured Digvijay Singh and not Subhash Yadav, lamented that his ambition of seeing an OBC as chief minister remained unfulfilled and retired to his Kervan Kothi mansion. Subhash Yadav was literally crying before his friends in a nearby hotel that evening, shouting repeatedly that this Thakur (Arjun Singh) always preferred a Thakur on crucial occasions. Could any one believe that any MLA would go against Arjun Singh’s wishes?

A well-read person with a scholarly bent of mind, Arjun Singh suffered from fits of megalomania. Then he lost perspective and started seeing himself at the centre of all things. When he resigned from the Union Cabinet and walked out of the Congress in December 1994, he did not have an iota of doubt in his mind that this would lead to exodus from the Congress and, at any rate, the government of Digvijay Singh in Madhya Pradesh would fall in no time. (He had by then developed a special aversion for Digvijay Singh whose elevation to the chief minister’s office he had facilitated through manoeuvrings a year earlier). But nothing of the sort happened. He and his MLA son Ajay Singh (Rahul Bhaiya) personally rang up each and every MLA belonging to the Arjun Singh camp but hardly half a dozen of them turned up at the Congress (Tiwari)’s national convention at Jabalpur.

It is surprising that many well-meaning people consider the disastrous Rajiv-Longowal accord as an achievement. Arjun Singh, then governor of Punjab, persuaded Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Harchand Singh Longowal to ‘quietly’ sign the accord. Longowal, who was heading one of the weakest factions in the Akali Dal, was not allowed even to consult his rump of executive; only Balwant Singh, his right-hand man, was permitted to be part of it. Thus half a dozen individuals decide the fate of troublesome issues like Chandigarh, Sutlej waters and Abohar-Fazilka and ‘direct’ the six crore people of three states (Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan) and the Union Territory of Chandigarh to follow it. Even Indira Gandhi had not been able to resolve these issues. The fate of Rajiv-Longowal accord is now a sad chapter in history.

The Bhopal gas disaster took place during Arjun Singh’s regime. How he betrayed the victims to serve the interests of Union Carbide Corporation and its executives have already been detailed at length.

Arjun Singh’s ambition was kept alive all these decades by Mauni Baba, a godman of Ujjain, whose past is as obscure as his ashram where only the privileged few are admitted. Arjun Singh was a frequent visitor to his ashram. Much like the witches of Macbeth, Mauni Baba hailed him with rajyog as his future everytime Singh visited him. The Baba does not speak as he has taken a vow of silence (maun) and so wrote his prophecy out on a slate board.

Arjun Singh was shocked when PV Narasimha Rao was retrieved from oblivion after Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination and made Prime Minister, with the approval of Sonia Gandhi. Narasimha Rao was then not even a Member of Parliament; he made Arjun Singh the Leader of the House till he was elected to Lok Sabha. Even after that, Arjun Singh remained Number Two (till he quit the Cabinet). That was the closest that Arjun Singh got to fulfilling his ambition.

But he was not satisfied. Before the Narasimha Rao government was a year-old, Arjun Singh was talking about a “realignment of political forces” which, he told a news agency in an interview, would be very right and healthy (development) for the centrist and left-of-the-centre forces to come together to evolve a broad consensus on national issues. Then the crux of his interview: “I will like to become the rallying point of the view that Congress should not cut away from its real moorings and remain firmly committed to the ideals of self-reliance, perceived by our great leaders and to our basic ethos.”

He apparently expected others to take the initiative and make him the rallying point but no one came forward. When the Babri issue was on the boil, some of his colleagues in the party, including then PCC chief Digvijay Singh, were said to have advised him to take the plunge and become a rallying point for secular forces. He hesitated. When he did quit the Cabinet, and the Congress, a few years later, it was too late. His role at the time of the Babri demolition still remains a mystery. He was asked by the Prime Minister four days before the demolition to go and personally see if then Uttar Pradesh chief minister Kalyan Singh’s claim of foolproof security around the mosque was valid. Arjun Singh went to Lucknow, had a tete a tete with Kalyan Singh and returned to Delhi without even visiting Ayodhya or Faizabad.

His quitting the Cabinet and the Congress must have been an act of utter desperation because he had done it on the fifth day after his mother’s death. No devout Hindu – and Arjun Singh was a devout Hindu from all appearances — takes any major initiative at least till after 13 days of a death in the family. When a journalist asked him about it at the “terahavin” (the thirteenth day shraddha ceremony) of his mother at his Churhat house, all that Arjun Singh said was that he would come to Bhopal and offer his explanation. But it was never to be.

A curious aspect of Arjun Singh’s actions in that period was his ambivalent attitude towards Sonia Gandhi. Even while out of the Congress, he advertised his loyalty to Sonia Gandhi. At the same time, he was demanding punishment for those who were part of the Bofors pay-off, knowing full well that the Bofors scam was the last thing that Sonia wanted to hear about. Singh told a TV channel in February 1995 that investigations in the Bofors case should be expedited. “Some names of beneficiaries have already come out and action should be taken against them in accordance with Indian laws. When some more names come, action should be initiated against them too.”

After his failed Congress (Tiwari) experiment, Arjun Singh went back to the Congress to wait for his rajyog. He contested for Lok Sabha from Hoshangabad constituency in 1998. A large section of the media reported during the interval between the polling and the counting of votes that there was going to be a hung Parliament and Arjun Singh had emerged as the consensus candidate of the non-BJP parties for the post of prime minister. When the results came, Arjun Singh had suffered what was the most ignominious defeat of his life, losing in all eight Assembly segments of the Hoshangabad Lok Sabha constituency.

Though fond of quoting from the Mahabharata’s Arjun to declare that he would neither show cowardice nor run away from the battlefield (>na dainyam, na cha palayanam<), Arjun Singh of the Congress was wont to run away at the first sign of crisis. One day he would proclaim that the decision-taking process in the higher echelons in the Congress was in disarray, and that he found that loyalty (in the Congress) was being evaluated with a very limited yardstick. As he was attacked by all, including his most ardent supporters like Ajit Jogi and Subhash Yadav, he made a hasty retreat and pledged his “unflinching loyalty” to the Gandhi family.

In December 1991, (he was then Madhya Pradesh Congress committee president as well as HRD minister at the Centre), Arjun Singh announced his decision to launch an agitation in the state to oust the BJP government of Sunderlal Patwa. The Congress leader stated he did not bother about consequences “once I have taken the decision.” The programme was to hold a demonstration at Kukadeshwar, Patwa’s village, by defying prohibitory orders, if imposed. Kukadeshwar was selected in view of the desecration of an old mosque allegedly by Patwa’s goons there. A sort of hysteria against the BJP government was built up by Arjun Singh and his party. The Youth Congress activists were asked to carry lathis to counter police lathis at Kukadeshwar. The administration prepared itself to handle the situation firmly. The forces, including the mounted police, were summoned from neighbouring districts and buses were requisitioned to transport the agitators to jails. Patwa deputed his trusted Cabinet colleagues to take charge of the situation there.

As the crescendo nearly reached a climax, Arjun Singh beat a retreat and abandoned the programme in favour of an innocuous public meeting, at a place sufficiently away from Kukadeshwar. The state government responded by dismantling its own preparations. Singh, in his speech, criticised the Patwa government rhetorically but made no demand for its ouster, nor did he spell out the objective of the party’s agitation which he said would continue at different levels. To give a farcical touch to the entire show, Arjun Singh later asked the then state home minister Kailash Chawla: “I hope there was nothing improper in my speech.”

A long innings

- 1957-85: Member, Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly

- September 1963 – December 1967: Minister of State for Agriculture, General Administration Department (GAD) and Information & Public Relations, Madhya Pradesh

- 1967: Minister of Planning and Development, Madhya Pradesh

- 1972-77: Minister of Education, Madhya Pradesh

- 1977-80: Leader of Opposition, Madhya Pradesh Assembly

- 1980-85: Chief Minister, Madhya Pradesh

- March – November 1985: Governor of Punjab

- February 1988 – January 1989: Chief Minister, Madhya Pradesh

- June 1991 – December 1994: Union Minister for Human Resource Development

- June 1991 – May 1996: Member from Satna, Tenth Lok Sabha

- June 1996: Lost from Satna, Eleventh Lok Sabha

- April 1998: Lost from Hoshangabad, Twelfth Lok Sabha

- April 2000: Elected to Rajya Sabha

- 15 May 2000 – February 2004: Member, Consultative Committee for the Ministry of Home Affairs

- 31 August 2001- July 200: Member, Committee on Rules

- April 2002 – February 2004: Chairman, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Purposes Committee

- 22 May 2004 – May 2009: Minister of Human Resource

He was re-elected to the Rajya Sabha from Madhya Pradesh without opposition on March 20, 2006.

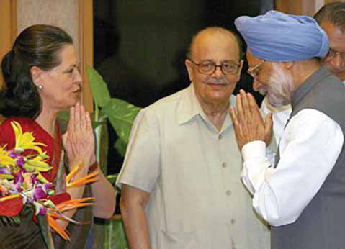

Sonia Gandhi, Arjun Singh and Manmohan Singh

Sonia Gandhi, Arjun Singh and Manmohan Singh